Tech's reality problem

But maybe the reality is we have a problem with tech.

Been avoiding the news lately? Can’t say I blame you, but I’ll have to burst that cosy bubble and tell you that Trump renamed the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America.

There, that wasn’t so bad, was it?

Since I stumbled across (and wrote about) the story, I’ve not been able to get it out of my mind. Not so much the news itself — like, honestly, who cares? it’s an ocean basin, call it what you want, you don’t need to listen to Trump — but more how map apps have played a key role in the change, making the Gulf of America feel real to people.

And if there’s one thing I can say with certainity, it’s that tech companies are creaming themselves about that. So let’s all take a big leap into that stinky, sticky mess.

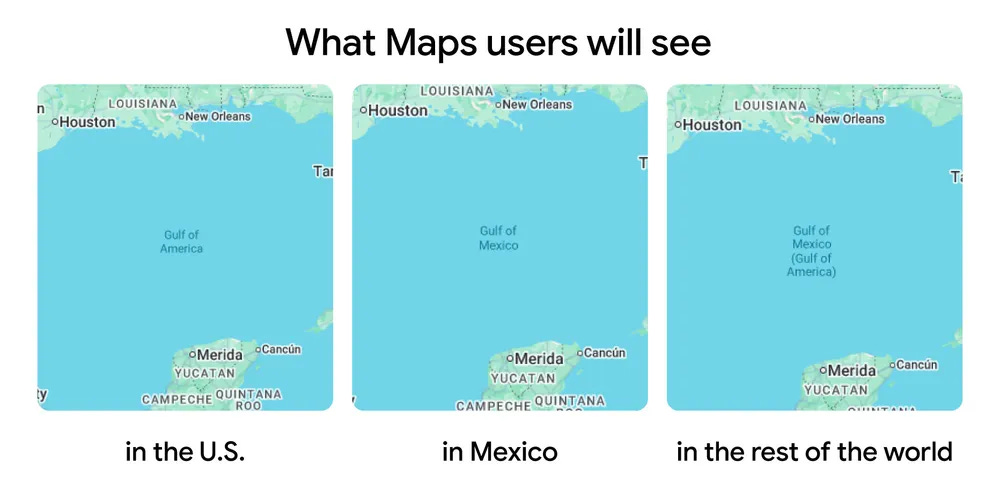

Shocking absolutely no one, social media is aflame about the Gulf of America story. But if you take a second and scroll through how it’s framed, you’ll see scores of posts viewing the name change through the lens of Google Maps, Apple Maps, and whatever the hell Bing’s map app is called. Probably Bing Maps.

Editor’s note: Yep, it’s called Bing Maps.

The fact apps altered the name to the Gulf of America is important to folks.

But here’s the interesting thing. Places in the U.S. are managed by The Geographic Names Information System (GNIS), a tool that maintains a database of locations for the country. After Trump’s executive order about the rename came through, this was altered on the GNIS on January 20th.

Google was the first to update its maps with this information, something it did around February 11th — which is when the backlash started.

The point is this: the name change didn’t become real for people until Google said so.

I’ve had beef with Google Maps before. When I was in Sicily last summer I trusted the navigation app over what I could actually see, which led to us getting our car stuck on a rocky trail in the baking heat. Since then, I’ve been suspicious of the service and my relationship to it, noticing more and more how it warps the world around me.

Thankfully, some smarty-pants made a term for this sorta thing: hyperreality.

This concept, coined by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, examines the blending of fact and fiction. Putting that another way, it covers the moments where “real life” (you know, the thing our bodies actively experience) blurs with simulation, AKA screens.

The Gulf of America is a prime example of this. People only kicked off when map apps informed them of the change. When the screen defined their reality.

Officially, its name was changed weeks before. In actuality, nothing changed when Google Maps made the switch. The ocean basin remains an ocean basin: wet and basin-y.

And you can still call it whatever you want.

It’s like a stadium rebranding. For example, Twickenham — the home of English rugby — is now the Allianz Stadium. And you know what? That’s the first time I’ve ever used that name. It doesn’t matter. It’ll always be Twickenham to me.

Of course, a water mass bordered by two countries is different to a stadium (you know, with all the “political” “ramifications”), but that’s not entirely the point. The thing to keep an eye on is that reality was warped by tech companies, they made the story matter to people, and they’ll be rubbing their grubby little hands together in glee about that.

My most immovable tech theory is the industry’s overall goal is to become a full body glove, something that’s continually between us and the world. It’s why they’re so in on AR and VR.

We began this modern era with desktop computers, bulky machines that couldn’t go anywhere. From there, laptops, vaguely portable, but still easy to disconnect from, followed. Hot on the heels of those came the real sea change: phones. Things we carry all day, every day.

But that’s not enough. There’s still more data to be had, more profit to be extracted from us. And the easiest way of doing that is being involved in more and more of our lives.

It’s the goal of the Vision Pro, the Meta Ray-Bans, or any other smart wearable device. It’s even happening with AirPods, where Apple introduced a series of features that will encourage users to wear them as much as possible.

If tech companies can control the information that’s passed to us, then they control reality. Fact and fiction become entangled — and they can define what’s what.

The reaction the Gulf of America’s appearance on Google Maps shows this is already happening. We’re living in the hyperreal, a state where what we view on a screen, what an algorithim says, is as important and impactful as what’s actually around us.

The more you search for hyperreality in society, the more you see it. From artists that are huge on Spotify that no one has ever heard of to the fake creators of the toaster, the imaginary is beginning to outweigh the defined.

But — and this is key — only if you let it wash over you.

Since I’ve started working on The Great Uncoupling™, the more I’m convinced of it. There’s no need to abandon technology, instead we simply need to become more aware of it, mitigate its impact.

There’s no reason Apple Music should decide what we listen to, Netflix what we watch, or Google Maps what we call something. The choice is yours. The important moments, the truly vital things, are those around you, the relationships you have, your local neighbourhood.

Yes, hyperreality is a modern state of being, but only if you allow it to be.