The smell of long-smoked cigarettes blanketed the shop. It’s a particular odour, one that comes from years of burning tabs inside. There’s something deep and cavernous about the smell, a whisking of baked wood and wet sourness — and it was the first thing I noticed when I walked into the stationery store.

Well, that, and the old fella behind the counter who’d just sparked a cig.

I moved into my current area of Amsterdam about five-and-a-half years ago. One of the best bits about living in a new part of town is immersing yourself in a fresh and different environment.

Visiting somewhere is good and all, but it’s a surface level experience. It’s different to truly absorbing the locale; there are intimate rhythms, a gentle sway of people and businesses, that slip under the radar when you just pop around.

One of those things for me in the area was a little shop called Nibo.

Even though it was opposite a supermarket, it didn’t stand out. Maybe it was the old sign or design, but it slunk into the background of the street. But, as soon as I spotted it was stationery store, I was cartwheeling with joy. If I could cartwheel. Which I can’t. But I live in hope.

After (metaphorically) cartwheeling around, I could reflect on what was a great moment, because I love a stationery store.

I don’t know whether it was being dragged around them as a kid, those Viking catalogues my parents got sent, or just my love of writing and reading, but office supply shops have always struck a chord with me. So having one minutes away? A dream. A staple-filled, paper-lined, accessory-fuelled dream.

Reality begged to differ.

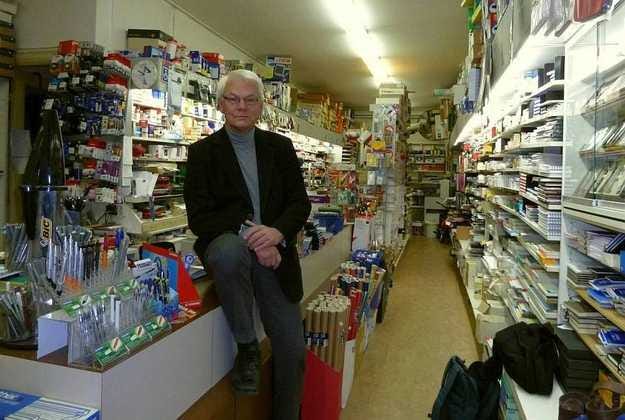

Nibo was old and dusty, a far cry from the boutique, cutting edge stationary store I imagined. I wanted freshly imported Japanese paper, award-winning design items, and aesthetic products to make my desk pop. That wasn’t Nibo. It seemed like a passion project, albeit not a particularly passionate one.

Nibo wasn’t bad, per se, just eclectic. Old school. The smoking fella didn’t seem to care about modernity or advancement, instead he stocked a cacophony of traditional office supplies, many of them sunbleached and grubby.

It was a curiosity spot. A charming throwback, not somewhere I’d frequent regularly.

Over years, I popped in to pick up something I needed every now and then, but I was more just happy it was there. Nibo remained static in a regenerating area. No matter what happened around the corner, each time I visited it was the same, emanating a dark tar tang of stale smoke and yellowing supplies.

For each and every one of us, there’s a last time we do something. We rarely recognise it at the moment, but at some point there’ll be a last exam, a last hug from a friend, a last visit somewhere — and I remember mine at Nibo clearly.

My record collection sits in a series of cabinets next to a substantially-sized window. After spotting how the sunlight hit the vinyl at certain times of the day, I realised I needed to protect them. As a quick fix — and one that, sadly, still exists today — I decided to get some cardboard squares to cover the shelves.

So I headed to Nibo.

The old fella who owned the shop was behind the counter, surrounded by paper, a cigarette dangling from his fingers. I enquired about cutting cardboard to a specific size, and he told me he could sort it. But as soon as he began moving it was clear he was terribly ill.

He struggled to such a degree that I took over operating cutting machine myself. It was a sad scene, but I didn’t dwell on it. Time comes for us all, I suppose. I got what I needed and went on with my business.

A few months later, I noticed Nibo’s shutter hadn’t been lifted for some time. This wasn’t hugely surprising (from what I could tell, it only opened when he felt like it), but the closure dragged on longer than I’d seen before.

Next thing I knew, workers were gutting the place. Nibo was gone.

I can’t say for certain that the owner died, but it’s seems likely. A stalwart of the neighbourhood was gone. History simply fluttered away with the rumble of a trade truck.

But here’s where things get fascinating.

Last weekend, my parents travelled over. As is the case whenever anyone visits me, I turn into an Amsterdam tour guide. I can’t help it. I get excited and just want to splurge out everything I know about where we are.

But when the conversation turned to the area I actually live in — the Frederik Hendrikbuurt — I realised I didn’t know as much as I wanted about its history. I vowed to fix that and become, step-by-step, even more insufferable.

A quick search dug up a site called Geheugen van West, which is “Memories of the West” in English. The site, which is still going, has hundreds if not thousands of articles about this part of Amsterdam. It’s a treasure trove.

I narrowed the search filter down to the Frederik Hendrikbuurt and was surprised to see a familiar face: it was the man from the stationery shop. There was an entire article about him.

Reading the piece is like gazing through a window into the past.

Nibo’s owner was a man called Jaap Nieuweboer. The business was started back in the 1920s, with Nieuweboer taking over the store in 1967. There was a period of success in the 70s and 80s, where he ran a printing shop, as well as some other businesses, and employed a large staff. But after he got divorced in 1988, these businesses were split between them, and Nieuweboer ended up with the stationery store.

Over the years, the author tells us, he amassed a specific collection of hardware and office supplies that drew people from all over the city to his shop.

The article finishes with Nieuweboer stating he was financially stable enough to view the business as a hobby, a way of connecting with the neighbourhood. I saw that firsthand. The piece was written in 2011, and when I first met Nieuweboer it would’ve been around 2019. Whenever I visited Nibo, there seemed to be someone he knew in the store. It was like his front room — and not just because he was blasting cigs.

I loved reading the article. It gave depth to something I’d unwittingly experienced as two-dimensional. Stumbling across this little corner of the internet expanded and lit up my world. But, unusually, my precise surroundings, not just metaphorically.

Something about that feels odd.

Honestly, it’s likely that Nieuweboer is dead. His shop, Nibo, is gone, along with his physical presence in the area has disappeared. Yet he persists.

Besides those who knew him intimately, his legacy and impact remain online. And, in this very article, it’s expanded, stretching further.

The internet is operating as a blend of oral tradition with written history that’s uniquely accessible, yet at the same time hidden underneath so much else that it’s tough to find.

It’s a little like online archaeology. These stories are everywhere online, but they won’t necessarily fall at your feet. You have to hunt to come across them, scraping away the dirt that search engines throw up.

Nibo will change — knowing Amsterdam, probably into a café — and all physical memories will be swept away. Yet here, online, in this space, the stationery store that lasted for over 100 years will survive. It’s a relic, a digital remnant of a real place.

I’ll never walk into Nibo again. I’ll never buy cardboard from a man in a shop that billows with cigarette smoke. But, thanks to the archival qualities of the internet, I feel more connected to my area and a strange, ethereal closeness with a man I never really knew.

I’m not sure precisely how I feel about all this, apart from the fact I now kinda want a cigarette.