On July 8th, Pocket is shutting down. And with that, the curtains swish closed on another internet era.

This has me split. In one hand, I hold a glass to toast an important part of online history. In the other? A tiny gravestone and violin. To, uh… mark its end? Mourn it? I dunno, the whole thing fell apart. Maybe it’s about giant hands?

Anyway, let’s talk Pocket.

If you’re of a certain age, you’ll remember a time when the internet heaved with size. There was no centre, just millions of things to stumble upon, sprawling, feeling like a place where anything was possible. There’s also a chance you remember the mid-2000s when these possibilities turned into real things.

Online shopping was accepted, social networks began to connect us, and, most excitingly of all, a new form of writing was burning through the internet.

An element of these online days that’s rarely talked about is the evolution of internet blogging into journalism. The barrier to entry was so low that writers could gain audiences just by cranking up their own site. There was fantastic and idiosyncratic writing everywhere (and, yes, a lot of crap too), but it was the first unified expression of internet freedom.

The success of blogs led to new media outlets forming. Here, journalists were paid to explore, to push the boundaries of writing, with little of the limitations that legacy media had. It was a glorious Wild West — and there was so much to read. So damn much to read.

One way I kept abreast of it all was RSS feeds. These allowed me to quickly keep track of what my favourite sites were publishing. But, while terrific for news, RSS feeds aren’t great if you don’t have the time to read the article right there and then.

And this is where Pocket came in.

In its purest sense, Pocket was a glorified browser extension. When you saw an article you liked, you clicked the little Pocket logo and it saved it. You could then either visit the Pocket site or the app to read the pieces later. This was particularly useful if you were commuting, as your phone would download all the articles to be read offline.

Even better, Pocket had a solid recommendation service, so once you’d plugged in a few pieces you found interesting, there was a gamut of other intriguing writing to read.

I used it for years. Pocket was a core part of my app repertoire.

But, friends, those days are long gone. Mozilla is shutting it down. And even I barely care, because, spiritually, Pocket died aeons ago.

Since Mozilla bought the app in 2017, the online writing industry has nosebombed. Yes, things like Substack exist, but good writing being the beating heart of the internet just feels… outdated.

This is something Mozilla references in its explanations: “The way people use the web has evolved, so we’re channelling our resources into projects that better match their browsing habits and online needs.”

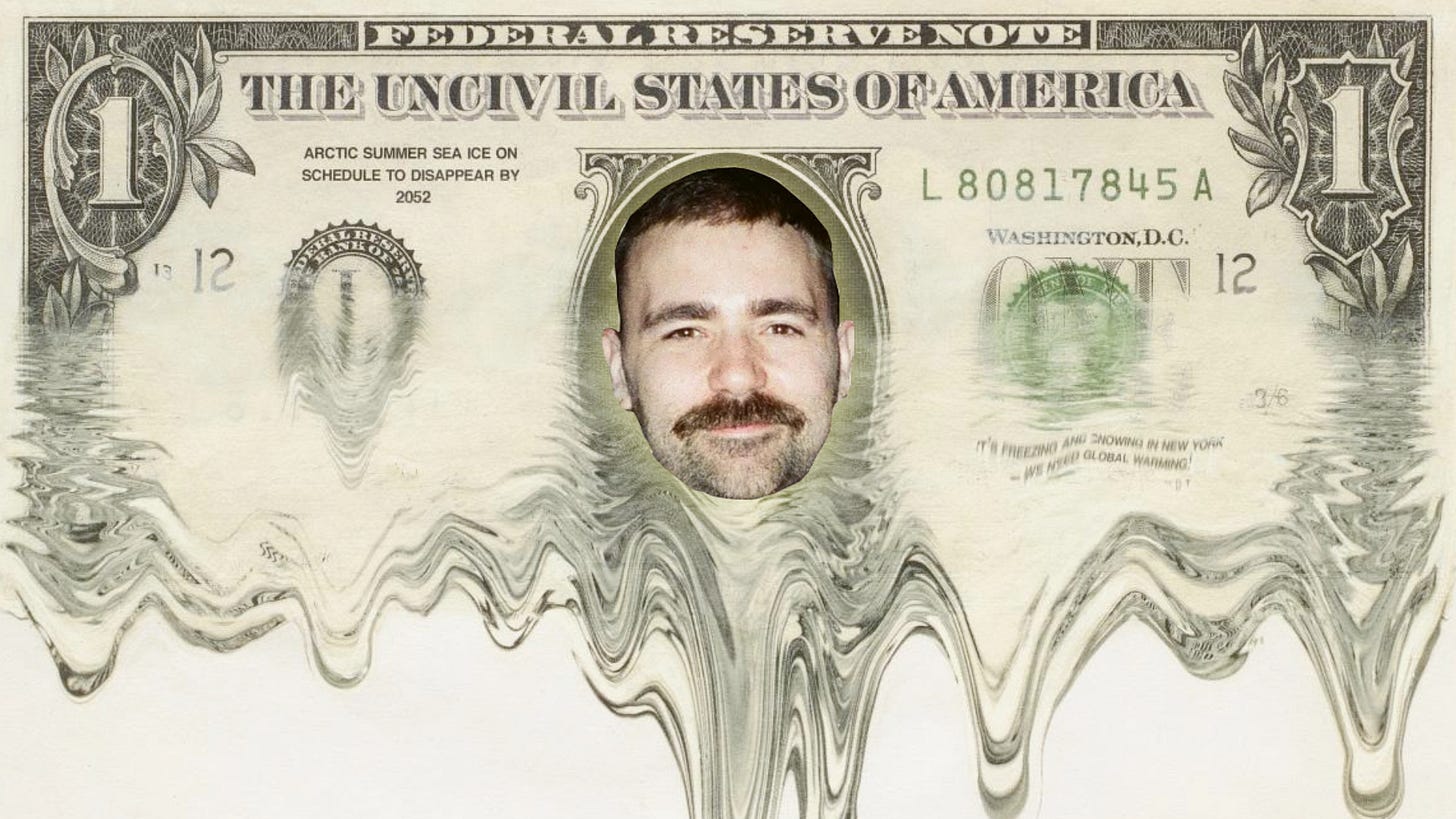

Pocket is a relic, a holdover from a simpler time. Though, of course, it’s all about money. It always is.

If you had to pick era-defining sites from this late-2000s to early-2010s writing boom, it’s tough to look past Buzzfeed and VICE. These new media publications dominated the period.

It also helped that they were valued at hundreds of millions of dollars.

This began a goldrush, one that led to a swell of well-funded, skilfully constructed, and Very Online writing.

Outside of the inevitable VC involvement, this was paid for by adverts. The more people read articles, the more money sites could earn. So they hired people to write articles that people wanted to read. To make money.

It’s the genesis of clickbait, but that’s a story for another day. The only thing we need to take notice of is the entire model was deliberately imploded.

There are a few different moments you could pinpoint this happening, but the clearest is the “pivot to video” phase of 2015.

Led by Facebook, this was the prioritisation of video content over the written word. Almost overnight, social traffic to major publishers plummeted. So did ad spend.

This led to a range of publishers firing editorial staff and trying to go the video route instead. In one fell sweep, writing had been displaced as the core of the internet — even if it was based on a lie. Genuinely. Facebook knowingly inflated how many people were watching videos to inspire this shift.

Of course, the removal of articles as the culture at the centre of the online world didn’t just end immediately, but pivot to video was the beginning, a moment that shaped today’s internet.

On one hand, I can’t be too angry. It was bound to happen at some point. Whether it was then or a few years down the line, the fact is it’s easier and more lucrative to show people short videos than have them read articles or blogs.

When the entire online economy is focused on attention and keeping people hooked, TikTok is going to be more valuable than something like Pocket.

On the other hand, it feels like that shift has made the internet worse. Where we once shared articles and engaged with the written word, we now flick through an endless feed of low-quality video slop. And you know AI is only going to make this worse.

Yet, the techno-optimist in me says we’ll be fine. That we’ll get through. That this is a blip, not a race to the bottom, but I struggle to find evidence for that.

Whatever happens, one thing’s clear: Pocket shuttering slams the door of the internet’s wordy era. The academic, text-first, forum-filled aspect of the online world is, as a mainstream concern, utterly over.

The internet is now a conduit for digital addiction, a haven for short-form videos aimed to keep us scrolling on our phones. Pocket closing doesn’t change any of this, but it remains an interesting moment to look at and say, “goddamn, things sure done changed.”

Because, goddamn, things sure done changed. Pocket’s death is a gravestone for a gravestone. A border we can’t cross over. A historical footnote in the internet’s history.

Pocket, we hardly knew thee.